As the dwarves, Bilbo, and Gandalf near Beorn’s house in chapter 7 of The Hobbit, Gandalf is telling the little bit that he knows about their soon-to-be host. After telling them that Beorn is a skin-changer, he makes the following curious statement: “At any rate he is under no enchantment but his own.” Gandalf then goes on to describe that Beorn is the lord of his own lands.

But that Beorn is simply a man (or bear) with no master, beholden to no king, cannot be what Gandalf meant by saying that he was under no enchantment but his own. That would only be to say that he was under no governance but his own.

Beorn’s conversations with the dwarves reveal that he has a complete detachment from material things, especially those that others consider valuable. He is not interested in gold, silver, jewels, or cunningly-made objects. He possesses no things of gold or silver in his hall. This, while revealing, is also not, I think, what Gandalf meant, even if it is true to say that the dwarves are under the enchantment of the gold of the mountain and Beorn is not.

Finally, I do not think that Gandalf means Beorn is under some sort of self-delusion, which might be what we mean these days if we were to say of someone that they were “under no enchantment but their own.”

Magic in Middle-earth is always about power, but it is not the power of politics or wealth. It is the power of the will. The Elves of Lothlorien seem to say as much when they are taken aback at how the hobbits refer to what the enemy and the elves do by that same name: magic. Theirs is simply the power to realise their will in the world, and because the freedom to exercise this power seems foreign to the hobbits, they think of it as magic, though it is put to very different purposes than the magic of Sauron and his servants.

Beorn’s enchantment is the freedom of his goodness. That Beorn is one of the “good guys” is, I think, obvious, though there is also a way in which the words “good” and “evil” don’t really seem to apply. Much like Tom Bombadil, Beorn seems to be (a) his own master and (b) a servant of Good, thus (c) not actually his own master at all but (d) also paradoxically and totally free.

This seems to stem from the fact that Beorn, like Bombadil, has no will to power over others. He seeks only peace, harmony, and flourishing of the world around him. It is surely no mistake that both characters are situated in nature and have power over that nature.

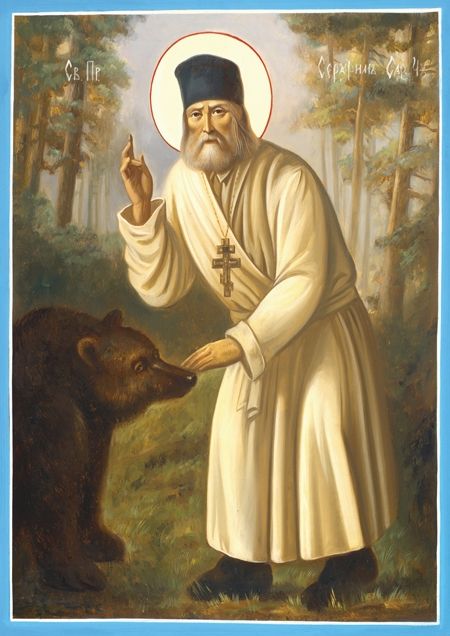

They seem to be somewhat like the Saints, several of whom (like St Jerome or St Seraphim of Sarov) were known for an intimate communion with nature. In the Saints—as in Beorn and Tom Bombadil—the natural world is reunited to the human as the human has become reconciled to God. One cannot perhaps push the comparisons all the way, but Beorn’s innate goodness is clearly the source of the “enchantment” that he is under.

It is his own because he is good. It is an enchantment because it is an expression of power in the world. It is freedom because goodness gives freedom (whereas evil binds.) It is not a delusion because there are no signs that he is unaware of or detached from reality. Rather, his enchantment allows him to commune with reality in a way that the dwarves simply cannot understand, with their love of and desire for gold and wealth and power.

Gandalf suggests that Beorn is dangerous, and I suppose that truly good people are dangerous. Beorn’s first assessment of Gandalf, however, is that he doesn’t look dangerous, and I suppose that nothing is really dangerous to the truly good. Their priorities are completely other from the rest of ours. The good are a danger to anyone who brings impurity or evil near them, for in their goodness—i.e. by the power of their enchantment—they reveal evil to be what it is.

The good are dangerous because they don’t play by the same rotten rules as the rest of us.

Leave a comment