Perhaps it’s because we Orthodox are in the midst of Great Lent, but this passage struck me as echoing the drudgery that a proper fast can sometimes feel like. Under the eaves of Mirkwood, the dwarves and hobbit have to be very careful. They prepared for a long, long journey but still it seemed longer than ever they planned for:

All this went on for what seemed to the hobbit ages upon ages; and he was always hungry, for they were extremely careful with their provisions. Even so, as days followed days, and still the forest seemed just the same, they began to get anxious.

The Hobbit, ch. 8

Much like we can start casting longing eyes aside at all the things we are doing without during Lent, so the dwarves (as their hunger grows) begin casting eyes further and further aside until they are lured into the forest, chasing the firelights of Elvish feasts. Of course, the Elves are really there but as they keep disappearing, their camp fires become more like a mirage, a promise that is not fulfilled.

And their straying into the forest leads directly to the tragedy with the spiders.

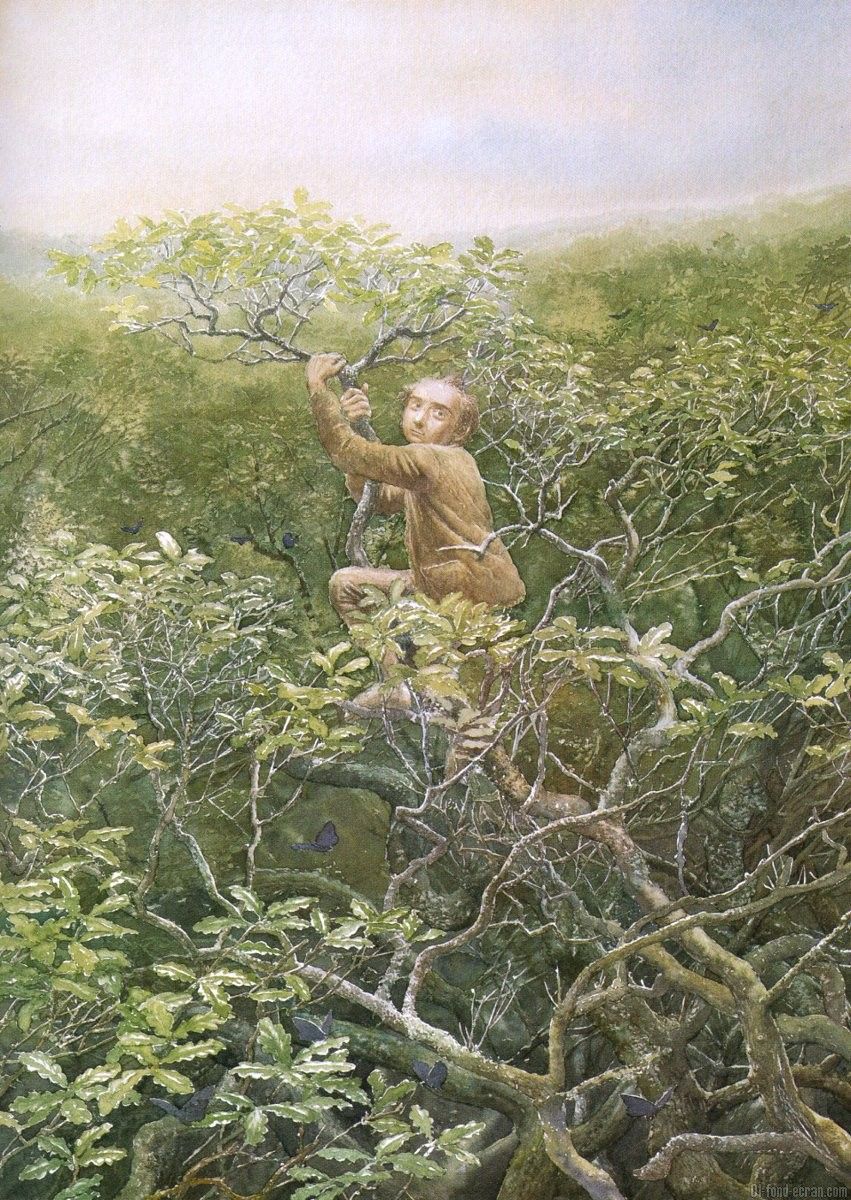

More interesting to me, however, is the fact that when Bilbo climbs the tree to peer into the distance and see if they are nearing the edge of Mirkwood, the narrator remarks that by a trick of the landscape, Bilbo was in a slight depression and did not realise how close they actually were to the end of the forest. This feeling of there being no end in sight accompanies a great many “lenten” experiences in our life, when we are forced through dark, endless days. The end may actually be very near, but we cannot see it for the depression that we are in.

And this is when we begin to feel, as Bilbo and his friends did, that “days follow days.” There is no difference one day to the next. Just trees. Endless trees.

The purpose of Lent—or any of the Church’s fasts—is preparation for a feast, for the arrival at some new enlightenment. Bilbo and friends think they have found that feast in the Wood-elves, but it is, as stated above, illusory and not the real end of their journey. The actual feast awaits them, in nascent form, at Lake-town once they have left the forest and the Mountain is in sight. The greater feast, of course, should come after the slaying of the dragon Smaug, the fulfilment of all their hopes.

There are, of course, several other Lenten images in Tolkien’s works: the long gruelling life journey of Aragorn is one, or Frodo and Sam’s march into Mordor. Frodo and Sam’s predicament especially echoes the drudgery of Bilbo’s journey through Mirkwood. Everything feels the same from day to day. There is no end in sight, or at least it feels that way (for Frodo and Sam the looming slopes of Orodruin seem always just out of reach). But at the end of their long journey, there is the hope of an end of evil days and a time of feasting and rejoicing.

Aragorn’s Lent is different; it is perhaps more the ideal of what a Lent could be, as he has a very clear goal and reward that lies at the end of his trek. And he does finally come into his rest, his throne, but only through the gruelling trials of the War.

The hobbits all suffer from being overwhelmed by their situations and become fixated on the moment, the present, without seeing the bigger picture. Sam, perhaps, is the only one who manages to see beyond (when, for example, he glimpses the light of a star over Mordor), but that is fleeting. In that sense, too, it is all too human. Indeed, when the Ring is finally sent into the fires of Doom, they lie down on the mountainside and wait for death. It is not a death of despair, but they see no hope of returning from their Lent.

But Aragorn endures years of suffering and trial, allowing himself to be honed for the eventual task of taking up the crown of Gondor and wedding Arwen. It is possible to see in Aragorn more of a monastic fast, but St Benedict’s Rule makes it clear that the monk is only striving to do what all Christians should. Only, it seems, the monk has a much clearer sense of priorities than the rest of us as he is reminded every day. In that sense, Aragorn understands what is at stake and what it will take to achieve his goals much more fully than the hobbits do, who enter into their Lenten journeys full of promise but are worn down over time.

Credit to the hobbits, though: they all stick to the task and pull through, which is more than many of us can say for ourselves.

Leave a comment