In my last two posts, I have been discussing Gandalf’s words at the end of The Hobbit: ‘You don’t really suppose, do you, that all your adventures and escapes were managed by mere luck, just for your sole benefit?” I have focused so far on the words managed by mere luck and suggested that luck had nothing to do with it. Rather, Bilbo’s success was a synergy between Providence and Bilbo’s own choices. Today to round things off, I want to focus on the last five words of that quote. Part 1; Part 2

* * *

As important as it is to understand that Bilbo’s successes were a combination of Providence and choice rather than anything so seemingly random and impersonal as Luck, it is even more important that Gandalf goes on to question Bilbo’s apparent belief that these things were just for his benefit—or maybe just the benefit of Bilbo and the dwarves.

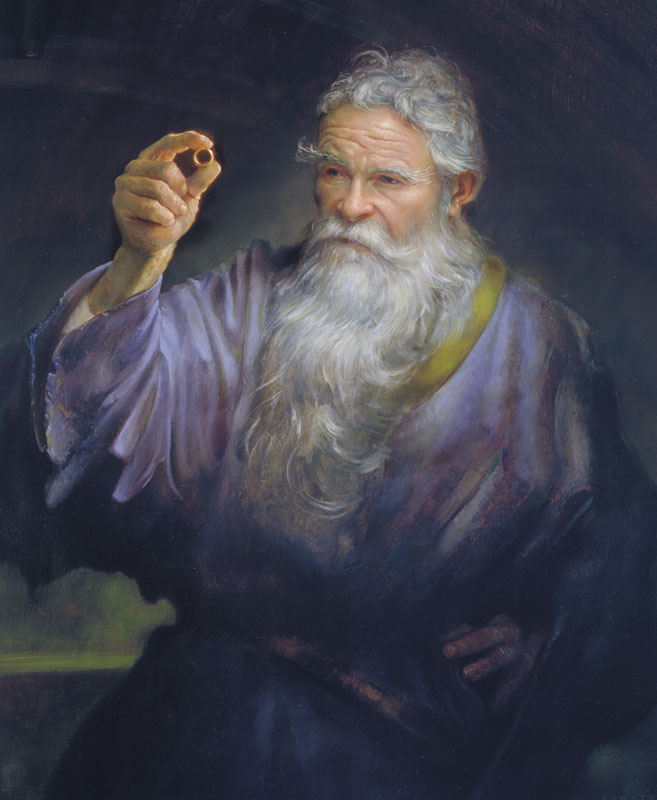

"Gandalf, Shadow of the Past" by Donato GiancolaNot so, Gandalf implies. It is worth remembering, too, that Bilbo doesn’t actually say that he believes this. So to whom is Gandalf actually talking? The Hobbit is filled with moments like this: I think Gandalf (Tolkien, really) is talking directly to the reader.

You see, we have a problem in the modern world, a problem Tolkien could see in the ’30s for it had already taken hold of the West. We do think the whole world exists for our own benefit, that the good things that happen to us (if we did not cause them to be because we are so good in ourselves) are for our own benefit (if not solely, then chiefly so).

I have a six-month-old daughter. This is her view of the world. It is infantile.

Providence is not for our own benefit. It is extended to us so that we may be a benefit to others.

Sure, it has to start with us. Gandalf says as much early on in the book, that this adventure will be very good for Bilbo (very amusing for Gandalf, too), but that is not the be-all and end-all of the matter. Bilbo does not become a mature hobbit so he can go back to the Shire and live in comfortable self-assurance. He does not become a wealthy hobbit so he can go back to the Shire and live in comfortable luxury.

He does not find the Ring so he can go back to the Shire and escape the Sackville-Bagginses anytime he wants.

Even without the wider view of the The Lord of the Rings to reveal the depth of the impact of Bilbo’s adventures on the lives of others, the message of The Hobbit is clear: good things happen to us in order that we may be a blessing to others. On one level, this is the kind of moralising that is common in classic children’s stories, but it is a message that Tolkien no doubt felt would be increasingly necessary. What we do, the choices we make, affect many more people than ourselves.

Bilbo’s adventures have a reach far beyond himself and the ten remaining dwarves of Thorin’s company—or the Men of Dale and the Elves of Mirkwood. By ridding the North of Smaug, the greatest threat outside of Mordor is removed from Middle-earth. By breaking the back of the Misty Mountain orcs, Bilbo and co. have significantly weakened Sauron’s still-considerable forces.

Being transformed as he is, Bilbo is able to prepare Frodo to be the Ring-bearer.

"The One Ring" by John HoweThe lesson here at the end of The Hobbit is that when we are blest with experience, wisdom, and wealth, we must consider these things gifts by which we may bless others and prepare them for their own adventures. In a culture that is obsessed with the Individual to the point of making every one a god, we are encouraged to be self-centred, selfish, and juvenile. That is the Bilbo Baggins of chapter one, not the Baggins of chapter nineteen!

In the extended edition of Peter Jackson’s Fellowship of the Ring, Bilbo tells Frodo that he doesn’t know why he adopted Frodo if not for selfish reasons. This is nonsense, and another example in a long list of examples to show that Jackson does not really understand Tolkien’s philosophy.

It was not selfish of Bilbo. It was exactly the opposite. The Bilbo of chapter one would never have adopted Frodo—or, if he did, he certainly would have done so for selfish ends. And it is more than just that Bilbo sees potential in Frodo, whatever that is supposed to mean.

Bilbo is fundamentally transformed by his experience, and his taking in Frodo as he does is part of his transformation. He has taken Gandalf’s words to heart, that his successes were not for his sole benefit. Frodo is Bilbo’s chosen heir, but he not chosen because he has “potential.” He is rather trained by Bilbo, instilled with a love of Middle-earth that is more elvish than hobbitish.

Bilbo and Gandalf call Frodo “the best hobbit in the Shire” and it’s no mistake that Frodo got that way under the influence of Bilbo. I’m going to revisit Gandalf soon, because there is so much foresight in what he does that it’s hard to imagine that he didn’t in some sense know that Frodo (or an hobbit like him) lay in the future when he showed up on Bilbo’s doorstep with thirteen dwarves.

Much like the generations of Hebrews/Israelites/Jews who were prepared for the coming of Christ, Bilbo is a kind of preparation for the coming of Frodo, the one who will destroy the Ring. That act by Frodo, the culmination really of Bilbo’s own adventures begun seventy-plus years before, which saved the lives of all living in Middle-earth, is exactly what Gandalf meant by saying that Bilbo’s adventures were not for your sole benefit.

* * *

Leave a comment