NOTE: Many references in this post and the last are likely confusing if you are unfamiliar with this story. At the very least, I encourage you to read the short form of Turin’s tale contained in The Silmarillion. The fuller version of The Children of Hurin is more detailed but follows essentially the same plot.

On our return trip from Arizona, we listened to the second half of the audiobook of The Children of Hurin—the really sad part! If there is some small smidgeon of hope in Turin’s life in the first half of his story, the second half is weighed down by hopelessness from the moment he kills Beleg to the moment he takes his own life.

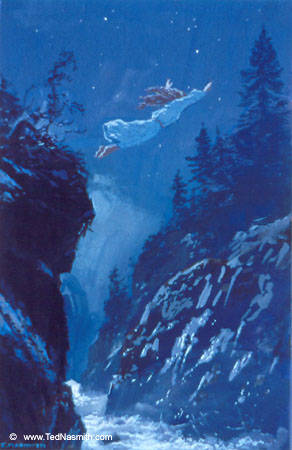

"Beleg is Slain" by Ted NasmithIn my previous post on this book, I touched very lightly on the idea of Fate, particularly in the form of the Evil Eye of Morgoth. In many ways, this is the most pagan of Tolkien’s stories, for it invites comparisons to the mythologies of Greece and Scandinavia more readily than the rest of The Silmarillion or the later Middle-earth tales, which reflect much more obviously Christian themes and ideas.

But on closer inspection, this is not purely a tale of Man striving against the impersonal force of Fate, as we see in the tales of Oedipus, Sigurd, or Kullervo, all of them truly fated to terrible ends from the very beginning of the story and with nothing in their own power to do about it. The tale of Oedipus, most familiar to modern audiences of the three, will serve as an example here:

At his birth, there is a prophecy of doom laid on Oedipus that he will kill his father and marry his mother. His parents leave him to die of exposure because of this, but he is adopted by another king and queen and raised as their own. As an adult, Oedipus learns of his fate from the Oracle at Delphi, and so runs away from home—straight to the very place where he was born, killing his father along the way and marrying his mother, the queen, as a reward for freeing the city from a monster.

In the above summary, we can see that every act the characters took to avoid fate in turn actually brought their fate to pass. In pagan mythology, there is no escaping Fate. But even within the story of Oedipus, he has choices to make and these are often driven by fear or pride. He runs away from home out of fear; if he had stayed, thinking that no man in his right mind would marry his mother, then fate might have been avoided. He kills his father out of pride, disliking being treated as a commoner when he is the son of a king. Point being, even in pagan myths, the characters are not mere automatons driven by Fate; their own choices play a major role in bringing about that end—but the fate will happen one way or another. If Oedipus had not run away from home, then Fate would have come for him in some way other than it did.

In Tolkien’s story of Turin, however, the word “fate” when it is used is used to mean otherwise than a future than cannot be altered; it means something more like “the end that they have suffered” without hints of destiny involved. Tolkien, in fact, prefers the word “doom,” which is an Old English word meaning “judgment”—in this case, the judgment of Morgoth. Nevertheless, whether through the use of the term “fate” or “doom,” the story explores the interplay between Free Will and Determinism (or fate, fortune, destiny, doom).

"Morgoth punishes Hurin" by Ted NasmithThe core question in a story like this (and those others mentioned above) is this: Could the hero have acted differently and thereby brought about a different ending?

In the story of Oedipus, the answer is an emphatic, No. The entire tale is structured so as to argue that no matter how hard we try to run from Fate, it will find us out in the end. There is no Free Will.

In the case of Turin, we know that his doom stems from the hatred and curse of Morgoth, and though Morgoth claims to Hurin to be “master of the fate of Arda,” he is not all-powerful to cause his will to be. Rather, what the story of Turin shows us is that Turin’s doom is an interplay between two wills struggling for dominance: the will of Morgoth and the will of Turin. The future is far from deterministic, and there are many, many points in the story at which Turin (or others, his mother especially) could have acted differently to bring about genuinely different and less tragic ends.

It is worth noting as well that whereas pagan myths often begin with a very specific prophecy that drives the fate of the characters, Turin’s story does not contain any such prophecy. It gives only the vague notion that Morgoth will bend all his evil will upon Hurin’s family. In other words, there is no prophecy that Turin will end up marrying his sister or killing his best friend. These things happen by ill chance or bad luck rather than by destiny.

In that sense, Turin is both more and less tragic than a character like Oedipus. Oedipus’ tragedy lies in the fact that he could never have avoided his fate no matter what he did. He is a character trapped. That helps to increase sympathy for him and what he suffers (and causes others to suffer).

For Turin, he is truly his own worst enemy. Had he been more noble, more like his fathers in temperament, much misery would have been avoided. It is less easy to feel sympathy for someone who causes trouble for themselves through hardness of character and bad decisions. But much of Turin’s misery is actually down to his mother’s choice not to leave her home and follow her son into exile. In this way, the decisions of one truly do have a huge impact on another.

And where does Morgoth come into this? He does not force choices upon characters, but rather takes advantage of the weakness of Turin and his mother Morwen to deepen his mischief. Therein lies the chief difference between Oedipus and Turin: for Oedipus, his fate is determined at birth by an impersonal force; for Turin, his doom is brought about through his own decisions and these are taken advantage of by an evil power to deepen his misery.

Turin changes his name many times through the narrative, but the most important of his re-namings is the last one. So important is it that Turin is often known by two names, his first and his last: Turin Turambar, that is, Turin Master-of-Doom.

Also of note is that the narrator calls Turin by his right name throughout the story save for the end chapters, after Turin calls himself Turambar. The characters inside the story consistently use whatever name they know him by, but the narrator is an objective observer. Thus, it is noteworthy as a point of extreme irony on the part of Tolkien the writer that the narrator switches to Turambar even as Turin’s doom overtakes him in the most extreme sense.

"Nienor's despair" by Ted NasmithIndeed, Turin’s sister Niënor is likewise called by her false name, Níniel, once she is found witless and unknown by her brother in the Forest of Brethil. I think there are two reasons for this, one a matter of prudence and one a matter of symbolism.

On the side of prudence, Tolkien is dealing with a very disturbing taboo, one of the last left in a society that has increasingly given its blessing to all manner of things that were in prior generations considered evil: that taboo is incest. By using false names in the final chapters of the book, Tolkien is only obliquely referring to the incestuous relationship of the siblings. Of course, the reader knows what is going on, but this narrative choice acts as a kind of euphemism in the story.

More importantly from an artistic standpoint, the names “Turambar” and “Níniel” are deeply symbolic to what is happening just then in the story. Turambar, as mentioned above, means Master of Doom. Níniel, on the other hand, means Maid of Tears. Turin’s name here is deeply ironic; Niënor’s name is prophetic or foreshadowing.

So how is this still a Christian tale after all, even while seeming to be one of Tolkien’s most pagan? The answer lies in which side of the Free Will/Fate debate this story falls. Oedipus’ story (and others of pagan mythology) clearly argue that Fate trumps human Free Will to choose. In the case of Turin and his family, the story argues two different but very related things to make the case that Free Will is still ultimately dominant:

(1) A person’s choices genuinely matter, but these decisions are often influenced by very deep personality traits that might at times seem to act almost deterministically. Nevertheless, it remains true that through an exertion of will, a person can act otherwise than they choose to do.

(2) Fate is not an impersonal, all-powerful force but is a personal will acting on a person from the outside, and thus the person has some freedom to acquiesce or resist that will (this goes for the will of Good as for the will of Evil).

When placed together, we see in Turin’s tale that Morgoth’s will is not destined to succeed in its designs but is only successful insofar as Turin’s own will decides in favour of bad over good. Many of Turin’s decisions are taken in innocence and with good intention, but the key is that they are his decisions and not imposed on him from outside. Morgoth can only twist what free agents choose to do; he cannot force anyone to act.

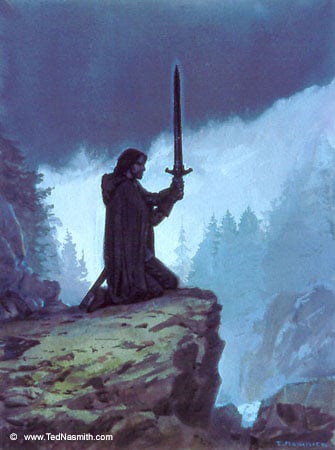

"Turin prepares to take his life" by Ted NasmithIn choosing war over secrecy at Nargothrond, for example, Turin is not choosing an evil over a good way. He is making a choice about how to confront Morgoth. It is only through this choice that Morgoth is able to bring about evil through what was not in itself an evil choice. If that is vague, then I means something like this: Every decision we make opens us up to outside actors (whether human or not), and every action invites a reaction. An act need not be evil in itself to have evil consequences, because just as Fate is not an all-powerful and impersonal force, neither are we all-powerful and impersonal.

The universe is full of persons, each vying for dominance, whether for good or evil. This is a far cry from the pagan myths of Greece and Scandinavia, and it is why the Children of Hurin remains a Christian story despite its many pagan-adjacent themes.

All of this is to say nothing of Morgoth’s most powerful agent of evil Glaurung the dragon, who causes many of the sorrows of Hurin’s children to come to pass. A whole post (at least) is needed to deal with the worm, and so I will save that for next week.

Leave a comment