In the final paragraphs of The Hobbit, Bilbo remarks with some consternation, “Then the prophecies of the old songs have turned out to be true, after a fashion!”

"The Shadow of the Past" by Donato GiancolaI have to admit that I personally hate—and I do mean hate and not just dislike—the use of prophecies in fantasy stories. It’s cliched at best, embarrassingly childish most times, and completely modernist in its understanding (that is, it is philosophical determinism, which is really just ancient fatalism without the capricious gods with with a mindless yet still capricious universe instead). Prophecies are usually fairly pathetic and overused means by which fantasy authors get their plots moving.

So why do I feel differently about the “prophecies of the old songs” that Bilbo cites? Well, for one these old songs are not being used as plot devices to get the characters moving. In so far as the dwarves have anything like prophecy, it is more hope and desire than anything. There is no moment when one of them says, “We have consulted the old books and know that the time is right, for it is written…” We can assume that even the hidden runes on Thorin’s map describe a phenomenon that happens annually on Durin’s Day, only there is no one there to see it (unless the keyhole is like the proverbial tree in the forest).

Even the “prophecies” of the Men of the Lake are little more than half-remembered days before the dragon that are being projected into the future as a hope of a time when the dragon will be gone again. And the people don’t seem very hopeful about this until the dwarves happen to show up and breathe life into old stories.

I could go on, but I actually want to focus on Gandalf’s response to Bilbo here: “And why should they not prove true? Surely you don’t disbelieve the prophecies, because you had a hand in bringing them about yourself? You don’t really suppose, do you, that all your adventure and escapes were managed by mere luck, just for your sole benefit?” [emphasis added]

There are two things I want to get into here, those portions I italicised in the quote above. And it is interesting that Gandalf is not really responding to what Bilbo actually said; he is responding to something behind the words, something unsaid.

First, Gandalf is reminding Bilbo that the world is an enchanted place. His experience in Hobbiton is very much that of the early modern person, living in comfort, for whom myths are just old stories that happened in someone else’s imagination long ago and far away. Gandalf is telling Bilbo that, no, the world is an ongoing myth and we are all part of the story.

We have a tendency to think that our lives are ordinary and plain, unlike the stories of old. As such, like Bilbo we can disbelieve in enchantment simply because we are personally involved in our lives. This is sometimes referred to in Christian circles as “practical atheism.” That is, we may intellectually believe in God, angels, miracles and all that, but when it comes right down to it, most of us forget to give God a single thought throughout the day on any decision we make, no matter how small or grand.

"Finding the Ring" by David T. WenzelWe say we believe in God but we live entirely without God.

We do not see our lives and our world as enchanted anymore, as filled with magic, with spirits and gods and powers. It is flat, materialistic, and any prophecy that comes true is a lucky guess that can be shown as such against dozens of failed prophecies of the same sort.

It is worth noting that the word prophecy, or some variant thereof, is used only four times in the novel:

- First, when the Smaug attacks Lake-town, the narrator remarks dryly that “not the most foolish doubted that the prophecies had gone rather wrong”;

- Second, to describe Bard as a man always prophesying doom and gloom;

- Finally, the two times right at the end of the book in the conversation between Bilbo and Gandalf quoted above.

The first is referring to the hopes the Lake-men had that the dwarves would successfully re-establish their kingdom Under the Mountain. The second merely describes Bard as a bit of a pessimist. Bilbo and Gandalf’s conversation, then, is clearly the odd one out in how the word is being used, because Bilbo seems to mean something grander than what was meant in reference to the hope of the Lake-men.

And this is confirmed in looking at the second emphasised bit from Gandalf’s response. The word prophecy is really being introduced here to point to a grander design that is beginning to take shape and that will be fulfilled in The Lord of the Rings.

All through our reading of The Hobbit, I constantly asked students to consider the role of luck in Bilbo’s adventures. It seems almost like a deus ex machina at times, only without the deus. On their final exam, I asked students to explain what Gandalf meant in the quote above (I’ll report on their thoughts once I’ve graded them all).

Tolkien is tapping into something biblical here, and not the mythologised understanding of prophecy that has inspired so many bad fantasy novels. Tolkien knows that biblical prophecy is not about predicting the future in some fatalistic sense. It is about hope, about promising that God is in control but that that control does not itself negate the free will responsibilities of the people involved.

Some have even suggested that Luck is almost a character unto itself. I constantly had to remind my students that this is a children’s book after all, and so some things are quite heavy-handed at times. But the point, as Gandalf will later say to Frodo, is that Bilbo was meant to find the ring. The most extreme moment of luck in the whole legendarium is not luck after all but a kind of providence that, from the inside, looks like luck.

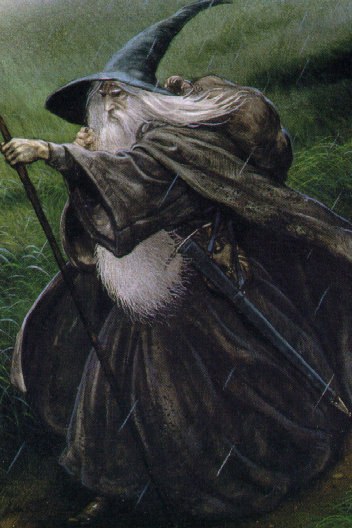

"Gandalf" by John HoweThat is why Gandalf can question Bilbo’s perception about prophecies. On the ground, to Bilbo, so much of it seemed like coincidence. But Gandalf as a divine being who sees much that is hid from mortals (though not all in the mind of Iluvatar) can see that there is an invisible hand guiding and protecting Bilbo throughout his adventures.

But Bilbo’s own choices still mattered: he chose to show mercy to Gollum, he chose to antagonise a dragon, he chose to give the Arkenstone to Bard, and he chose to go back to Thorin after doing so. None of these were choices forced upon him, and one of those (antagonising the dragon) is a decision that caused the deaths of many, many people. But other choices saved lives, in this book or the next.

And that is what Gandalf means by saying that Bilbo’s escapes were not just for his sole benefit. No, they were for the benefit of all, as we see when we finally come to the end of the story of the Ring.

Finally, mentioning the Ring here, I have to point out (having shown some scenes from the travesty that is Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy) that Jackson totally missed the point of this conversation. His Gandalf says he knows all about the Ring, as if to say, “It wasn’t luck after all. You had magic.” No, Peter Jackson, no. It wasn’t luck because it was Providence. And the Ring is part of that providence working itself out.

* * *

In my next post, I will look at another way to understand Gandalf’s statement, one less mystical and more practical. Nevertheless, I will contend that the practical and the mystical sides of this coin are just that: sides of a coin, both equally important.

Leave a comment