This is part 5 of a series on Tolkien’s Letter 131, most of which is included in the preface materials of The Silmarillion. Begin reading at Part 1 — or visit the previous post in this series.

* * *

After discussing the earliest days of Middle-earth and the Fall of the Elves through Fëanor, Tolkien now turns to the arrival of Men into the tales of Middle-earth. Over the course of a page or two, Tolkien makes several rather important and astounding observations, several of which bring together themes and ideas that he had hinted at earlier in the letter.

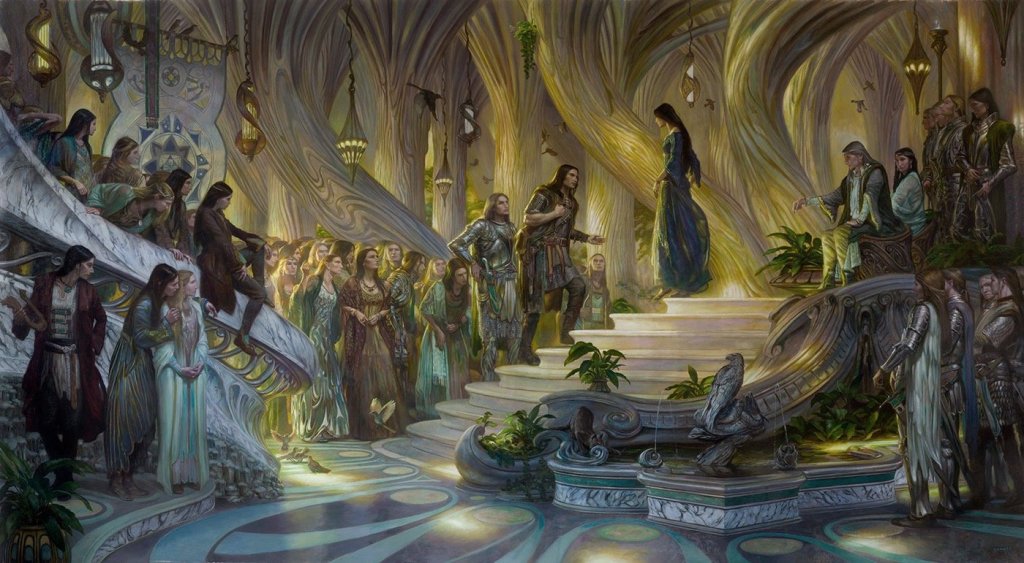

"Felagund Among Bëor's Men" by Ted NasmithHe writes of the appearance of Men: As the stories become less mythical, and more like stories and romances, Men are interwoven. We are not quite in the realm of “history” here, but the tales are becoming “more like stories,” which suggests a sort of historical air about them. “Romances” here refers to the romances of Medieval Europe, stories that involved our modern concept of romance as being about love, but the stories are chiefly about great heroes (as opposed to stories about gods and heroes—which defines mythology).

By the time Men show up in Middle-earth, the Valar have begun to recede into the background. They are still there. Tolkien does not say that the stories cease to be mythical only that the become less mythical. The word “myth” and words derived from it get used in very loose ways in our culture, usually as a pejorative to designate something as untrue. In its most basic sense, a myth is just a story that invites ritual participation. The importance of ritual is important; it is what sets a myth apart from a story or romance. It is a story that invites us into communion with the gods or God—in whatever form that may take in a culture.

The myth of the American Dream, forever, invites immigrants to participate in the rituals of American Capitalist life with the promise that if one does everything right and proper, they will be rewarded with the “paradise” of the family home surrounded with white picket fence. It is an earthly, secular myth, but it operates in the same way as the myths of religion. There are hints in Tolkien’s works that the Elves continue to participate in rituals tied to these earliest days, Galadriel’s mirror for instance being tied to the stories of the Valar, Manwë, and to the light of Eärendil.

Now soon after saying that the entrance of Men into the tales of Middle-earth lowers the narrative register from “myth” to “romance,” Tolkien adds: a recurrent theme is the idea that in Men (as they now are) there is a strand of ‘blood’ and inheritance, derived from the Elves, and that the art and poetry of Men is largely dependent on it, or modified by it. To which comment he appends the following footnote: Of course in reality this only means that my ‘elves’ are only a representation or an apprehension of a part of human nature, but that is not the legendary mode of talking.

This passage begins to lead Tolkien into speaking of the two marriages of mortal and elf. I am not entirely sure whether his parenthetical note about “Men (as they now are)” is intended to reference us, the Men of Tolkien’s latter days on this earth or whether he is speaking only of Men as they appear in his stories. I do not see any reason why it cannot be both, certainly not if these stories are supposed to form the mythic and legendary backdrops to our own days, 20th century England in particular. And if that is the case, Tolkien seems to be suggesting that without Elves there is no human art.

This is something that is so easily missed by modern, jaded, desacralised people. Is Tolkien asking us to believe in Elves exactly? Well, he does say that his Elves are really just a representation of human nature—but to speak this way is not in the “legendary mode.” What he is asking us to see is that the world is enchanted and more complex than we imagine. Our sciences have had the effect of making us think the world is far more simple and easy to comprehend than it really is. As a related example, I once read a prominent Anglican theologian opine that biblical angels are probably just metaphorical for God’s omnipresence.

Well, yes and no. Angels are experienced, by those who experience them, as something closely connected to but separate from God. In a similar way, I think Tolkien here is suggesting that Elves are very closely affiliated with Men but that they are experienced as separate. And that experience of “separateness” is precisely the “legendary” or mythic mode that Tolkien is seeking to capture. Elves are us but they are also more than us: they are us enchanted, us as we could be devoid of the effects of the Fall of Adam (Man).

I need to think more on this….

"Beren and Luthien in the Court of Thingol and Melian" by Donato GiancolaMoving on, after introducing the marriages of mortal and elf, Tolkien briefly discusses what is perhaps the central story of The Silmarillion: the story of Beren and Lúthien the Elfmaiden. Of this story, Tolkien says, As such the story is (I think a beautiful and powerful) heroic-fairy-romance, receivable in itself with only a very general vague knowledge of the background. But it is also a fundamental link in the cycle, deprived of its full significance out of its place therein.

There were three stories that Tolkien identified in The Silmarillion of being grand enough to stand alone—and all three have thus been published recently—as they are self-contained enough to be presented out of context. These are Beren and Lúthien, The Children of Hurin, and The Fall of Gondolin. Even so, Tolkien says that something is lost by removing these stories—most especially than of Beren and Lúthien—from the wider context of The Silmarillion.

I teach an elective high-school course on world mythology. There are some stories that can stand alone and some that cannot. Even something as seemingly independent as Homer’s Iliad is best received within a wider context of Greek mythology. It takes a few months of preparation for my students to be ready for the War at Troy. Some might say, “Just give them the story and be done,” and this is how that text is often taught in the context of a literature class. But that is not how it was written to be received. It was written for a culture that swam in the deep waters of stories about the gods and heroes, such that to fully appreciate the Iliad, one has to be able to receive it in the context that the story is set. Similarly, the motive behind Snorri Sturluson’s writing of the Eddas was to preserve the old myths of the Norse people, now being forgotten, so they could appreciate the old poetry with its oblique references and off-hand comments about old gods and heroes.

Without wider context, therefore, these great stories lose much—most?—of what makes them great. Dante’s Comedia is largely unreadable today to anyone unwilling to put in a lot of work because the poem is so deeply steeped in the culture and Christianity of a specific place and time and needs to be received in that mode.

So really what Tolkien is saying, it seems to me, is “Yes, one could take a story here or there from The Silmarillion and enjoy them on their own, but that enjoyment will be immeasurably enhanced if one reads the story in its full context.” The independent books recently published—let’s take especially The Children of Hurin—are presented as standalone tales, and the unsuspecting reader might pick up such a book, read it, and not really appreciate it beyond a bit of self-congratulation for finishing a tough book. I think it takes reading The Silmarillion in full more than a few times before one can read The Children of Hurin as an independent story and really appreciate it.

Finally, when he introduces Beren and Lúthien, Tolkien makes this extended remark—perhaps the most important and revealing thing he says in the entire letter:

Here we meet, among other things, the first example of the motive (to become dominant in Hobbits) that the great policies of world history, ‘the wheels of the world’, are often turned not by the Lords and Governors, even gods, but by the seemingly unknown and weak—owing to the secret life in creation, and the part unknowable to all wisdom but One, that resides in the intrusion of the Children of God into the Drama.

What a statement! And yet quite far removed from the nonsense we often tell our young ones today: “Go out there and change the world.” The world is far too big for one person to go out and change—certainly not with the goal of so doing; to change one’s country, state, even town is too much for most. And yet it is to the small that, most often, the lot falls to change the world.

I think the difference is in “motive”—to use Tolkien’s word albeit differently. It is through quiet folk, small folk, going about their lives that the world changes; to set out to change the world is an act of ambition. But Beren, Bilbo, and Frodo are not ambitious. The first seeks only survival after the death of his family; the second wants only to stay home in peace and quiet; the third has more spirit of adventure than the others but that spirit is bounded by his own country (the Shire) not by some grand desire to go out and change the world.

Whatever one things of him, there are few more important people in the past five hundred years than Martin Luther, who in worldly position was a humble monk and priest. He was no grand theologian or bishop or pope or noble lord. And yet more than anyone living in the past half-millennium, his acts radically altered the entire course of the western world. Now, whether one thinks that is for good or ill, the point being made is that this pattern of the small person introducing huge change is a true one, but I doubt that even Martin Luther drew up thinking he was going to go out there and “change the world.”

There is a secret life in creation, Tolkien says, that governs these things, and they are part of that fabric of reality that is known only to God—but which (I love this) is inherent in the fact that the Children of God have intruded into the Drama. What drama is that? The cosmic one, of course, the story of all things that ever have been, are, and ever shall be. The moment Men entered into existence, it could not be helped but that they would shake the cosmos—the small as oft as, or oftener than, the great. But all this is held in the mind of God, foreknown and allowed (see Part 3 of this series and the discussion of Free Will).

That is why Ilúvatar could say to Melkor that he could not sing any song that did not have its ultimate source in the One. It is why Tolkien could say in Letter 181 that Frodo succeeded in destroying the Ring despite the fact that at the last moment the Hobbit claimed it for himself and did not cast it into the fire. Frodo needed only to get the Ring to the edge of doom; Ilúvatar would ensure that it went over the edge into the lava.

The secret life in creation is the will of God working its way out through the allowed freedoms given to sentient beings. It is the most powerful and potent force in the world. It is what allows St Paul to say that “all things work together for good to them that love God.” It is the lost sight of this secret life that plunges folk into despair, depression, and nihilism (have you ever met a joyful nihilist?). It is the sight of this secret life that keeps even the most ardent atheist moving forward in hope of a better future. The hope that things will work out well is tied to the individual acts of men and women seeking the good. We may think it is in our own strength that we accomplish this, but God reminds even Melkor that all strains of music originate in Him, whether we like it or no.

Leave a comment